The Greatest Goddess, Inanna

Inanna is one of the most powerful and passionately worshiped goddesses in the Sumerian pantheon, with special powers over love, sensuality, fertility, procreation, and war. Her enduring powers and appeal survived across many cultures and time periods and she evolved into Ishtar under the Akkadians and Assyrians and with the Hittites, Sauska, the Phoenicians Astarte and the Greeks Aphrodite, among many others. She was also seen as the bright star of the morning and evening, Venus, and identified with the Roman goddess. In some myths she is said to be the daughter of Enki, the god of wisdom, fresh water, magic and a number of other elements and aspects of life, while in others she appears as the daughter of Nanna, god of the moon and wisdom. As the daughter of Nanna, she was the twin sister of the sun god Utu/Shamash.

222

Large and very rare votive Neo-Sumerian plaque from the Ur III, 22nd Century BC, era featuring the great goddess Inanna with 24 necklaces of ascending size, long hair and an elaborate head dress. Intended for display and worship, this is a devotional piece for the home of a worshiper. This item measures 5 ¼ inches long and 3 1/8th inches at the widest point.

223

Old Babylonian molded standing sculpture of the Goddess Ishtar, the Babylonian incarnation of Inanna, standing naked with arms with two bracelets each folded below her breasts and a necklace. Dating from 2000-1595 BC, this little statue is 4 ½ inches tall and 1 ½ inches across at its widest point.

224

Large and very expressive votive Neo-Sumerian plaque from the Ur III, 22nd Century BC, era featuring the great goddess Inanna, standing, facing forward, naked as she is frequently depicted, with both arms folded across her lower chest. As the goddess with the greatest power over sensuality, procreation and ceremonial sex, her depiction as a naked female figure, sometimes with greatly exaggerated female features, is widely known. This piece might even be said to be unusual because of the normal human like nature of her figure. This plaque measures 5 3/4th inches high and 2 34th inches wide.

225

Alabaster Early Dynastic Sumerian lion head statue fragment. This little votive statue would once have had eyes of inset lapis or black stones. The lion is the attribute animal of Inanna. This fragment measures 32 mm x 27 mm.

226

Sumerian molded votive plaque of a striding lion with jaws wide open, facing right. The lion is the attribute animal of Inanna. This item measures 4 ½ inches wide and 3 3/8 tall and dates from the Early Dynastic Period, 2900-2350 BC.

227

Terra cotta figure of a seated Ishtar, from the Old Babylonian period, 1900- 1750 BC, the period’s incarnation of Inanna, in a rare depiction of the goddess suckling an infant in the manner of the Egyptian goddess Isis. Cradling her infant with her left arm, the goddess wears long robes and is richly adorned with a diadem, armlets, earrings and necklaces. This figure measures 5 inches (12.7 cm) in height.

228

Red terra cotta statue of the Phoenician Mother Goddess Astarte standing with arms folded across her chest, from 1,400-900 BC. A deity of fertility and sexuality, derived from Inanna in Sumeria, then through Ishtar in Babylon, Astarte eventually evolved into the Greek Aphrodite thanks to her role as a goddess of sexual love. Interestingly, in her earlier forms, she also appears as a warrior goddess, and eventually was celebrated as Artemis. This figure stands 6 ¾ inches high.

229

Ancient Terracotta Susa Idol c.1500-1000 BC. Measuring 6 1/4 inches high, it is a molded terractooa female goddess with fine details. This votive figure is of the most powerful of all female deities, Inanna to the ancient Sumerians, Ishtar to the Babylonians.

Provenance: Private FL Collection, Ex Prof Sid Port, Ex Christies NYC.

Egyptian Funerary Cones

The Egyptians were particularly religious people obsessed by death and the goal with which they seemed to be preoccupied with for the after life was to create the perfect harmony they found in the Egyptian living environment. In general it was believed that the best existence of man after life is comprised of what was thought as the best and the most desired style of life on earth. We are very fortunate for the even, dry climate of modern Egypt. Tombs from all eras have survived in remarkable conditions despite the ravages of time and looters. We can now admire and collect wonderful Egyptian decorative arts and funerary objects. In stone, bronze, wood, ceramic and faience, we have sculpture, jewelry, furniture, and used ritual pieces. The wonder and magic of the Ancient Egyptians lives on forever.

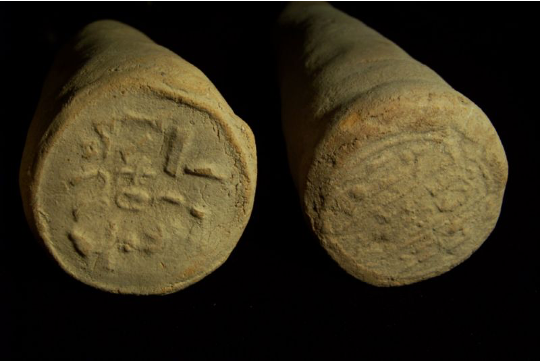

A distinctive Egyptian antiquity related to the tomb and quest for the perfect afterlife is fired clay cone-shaped objects bearing stamped funerary texts known as a “funerary cone.” The texts stamped or carved on the larger ends of these cones typically bear the name and titles of a deceased personage, often with additional biographical data and epitaphs. The texts provide a wealth of information concerning a variety of different individuals, their occupations, genealogy, etc. The only comparable parallel in terms of shape, composition and possible use is found in Mesopotamia, including Sumeria, which suggests a possible cultural link. There is considerable evidence that the use of such cones in Mesopotamia predates their appearance in Egypt by perhaps as much as a thousand years.

The creation and use of these objects, which exist in considerable numbers appears to be largely centered, if not entirely restricted to Thebes between the 18th to 26th Dynasties. These cones have been found placed over the entrance of the chapel of a tomb. Early examples have been found from the Eleventh Dynasty, but are generally undecorated. During the New Kingdom they generally start to reduce in size and to be inscribed with title and name of the tomb owner, often with a short prayer. The exact purpose of the cones is unknown but some scholars see the shape to embody a pyramid but there is no supporting data for this idea. The base of the cone remained visible in those few situations where cones were found as they were originally installed by tomb builders. The study of these objects has recently undergone a great resurgence with several wide-ranging surveys having been recently published and a new website uniquely dedicated to their study launched at http://www.funerarycones.com.

The Hendrickson collection contains three funerary cones, excavated at Thebes and estimated to date from the 18th Dynasty. That period, which ran from approximately (1550 BC to 1292 BC) is perhaps the best known of all the dynasties of ancient Egypt, including as it did a number of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs including Tutankhamun. Made from Nile clay or mud, these cones are of slightly varying sizes, from 5 to 7 inches in length and with slightly varying circumferences.

Almost all the cones have been crafted by hand. However, in some very rare cases, such as Davies & Macadam #138 and #215, it appears as if they were made on a wheel. This deduction is based on the fact that their bodies are hollow and their bottom surfaces retain the concentric traces of the wheel (See below: EA 9720 & EA 9730). Moreover, these hollow cones may have contained sand or liquid, such as water or alcohol, suggesting that they may have had uses other than to be set on the outer walls or courts of the tombs. Researchers believe that these objects initially played an important role in the funeral ceremonies as containers of sand, liquid, or gelatinous material, and were subsequently converted into cones.

Variation in the length of the cones is considerable. For instance, the longest cone, which was found at El-Tarif, is 52.5 cm (=1 cubit). On the other hand, the shortest cone, to the best of my knowledge, is the one of Padiamunnebnesuttawi that is housed at Manchester Museum; it is only about 7cm in length.

In 1885, the first systematic corpus of the stamped texts was published as compiled by the German Egyptologist Wiedemann. Another by the Frenchman Daressy followed in 1893. A corpus of facsimiles compiled by Davies and Macadam was published in 1957 and provides the key reference source for the study of these texts today, while new examples appear in the literature from time to time.i

A more careful look at these objects demonstrates that extensive physical variation exists which the word “cone” does not express. Indeed, such a categorization of all clay objects bearing these stamped funerary texts has served to blur their distinctions. We can note that these so-called “cones” are often rectangular, wedge-shaped, flat and bell-shaped,ii and possess a wide range of variation in terms of length, width, and thickness. There even exists at least one example of a double-headed cone.iii The objects survive in a variety of colors, many are painted, and some are even hollow. Some of the objects bear stamps on more than one side. The use of the word “cone”, then, suggests a uniformity between the objects which hinders their complete consideration. Noting this problem, I would like to offer a few suggestions toward a more holistic analysis of these objects.

First, rather than referring to the stamped texts as “cone texts”, they are perhaps best referred to as “funerary stamps”, as the same stamp may appear on a variety of objects of different shape. Realistically, the use of the word “cone” is likely to persist as it is firmly entrenched within the vocabulary and literature of the Egyptologist. A realization of a broader meaning for this term, then, is required if it is to be accurately perpetuated.

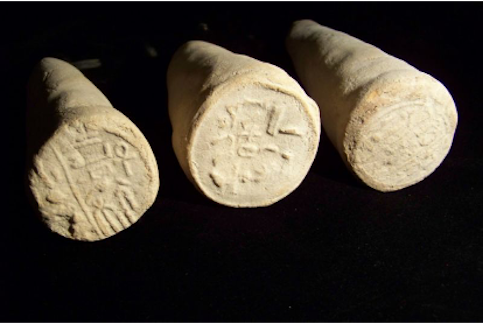

In 1934, Borchardt, Königsberger, and Ricke noted a variety of shapes and proposed that these objects served as frieze elements once situated on the facades of Theban tombs. Two 19th century observations of these objects seen in-situ in such a context, and an archaeologically recorded example of 11th Dynasty uninscribed objects in-situ, provide strong evidence toward this conclusion.iv

Additionally, friezes of funerary stamps seem to appear in certain Theban tomb scenes which apparently depict external views of intact tombs.v If we make the assumption that the proposition of tomb friezes is indeed correct, then it might be reasonable to assume that all objects bearing the same stamp constitute an archaeological assemblage. These assemblages, in many cases, are presently dispersed around the world. A consideration of these assemblages may eventually provide considerable information concerning external tomb architecture, function in terms of shape, and many other questions.

Archaeologically there is a vital need to study the object as a whole. If one looks past the inscription, a wide degree of variation is evident as noted previously. An archaeological approach would ask such questions as how do the objects with the same stamp differ and how are they the same? What variation exists between such objects, cone-shaped or otherwise, which bear different funerary stamps? How many? In archaeological terms, then, we are interested in the analysis of intra- and inter- assemblage variation.

Many archaeologists tend to intimately study even the most subtle of variations in pottery vessels, yet these clay funerary objects have received no such attention. Many collections contain these objects in the form of their stamped ends, the remainder of the clay having been sawn or broken off to reduce the inconvenience of bulk and weight. The relatively aesthetically unattractive part of the objects, then, has often been sacrificed by those blinded by the allure of texts. Petrie himself, though generally an outstanding archaeologist, freely admitted to his participation in this mutilating practice: “as the inscriptions are all that is really required, the bulk of the cone was removed, either by sawing, if soft, or breaking, if hard. Thus with a very small loss, I reduced a collection of over 250 to a more manageable bulk.”vi

Nevertheless, complete objects can be found in many collections and even the broken ones can provide significant data.vii Much of the analytical criteria applied to the physical analysis of ceramic vessels is certainly appropriate to the analysis of clay funerary-stamped objects. Material and mode of manufacture, size and shape, and coloration serve as broad analytical categories.

This image represents the utilization of numbers of cones on the outer surface of a Theban tomb. While few cones have been found in place, as they were originally intended to be used or installed, there are numerous contemporary illustrations of their application, such as the ones reproduced here.

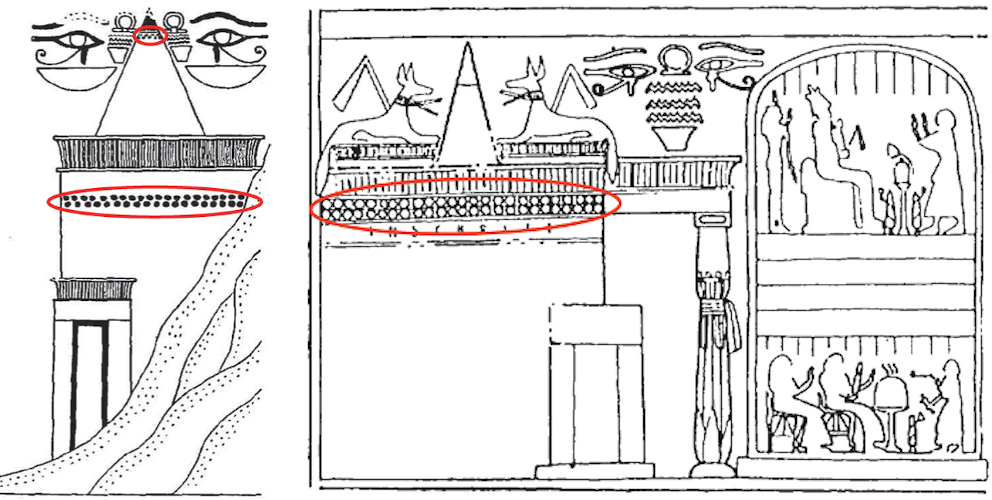

This photograph shows how cones were actually excavated in situ by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Those cones are currently on display at the Egyptian Gallerias at that institution.

References

i A summary of additions to the Davies/Macadam Corpus is found in Martin and Reeves (1987 p.64).

ii A variety of differently shaped objects bearing funerary stamps are illustrated in Borchardt, Königsberger, and Ricke (1934 p.28, Abb.8).

iii This interesting object resides in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow (D.1925.63).

iv See Reeves and Ryan (1987).

v Davies (1938).

vi (1988 p.23).

vii A recent publication on a large collection of “cones” by Stewart (1986) admirably describes the condition of the objects, e.g.”stamp only”, “damaged”, “complete”. Stewart also notes the measurements of complete cones.

Bibliography

Borchardt, L., Königsberger, O. and H. Ricke (1934) “Friesziegel in Grabbauten.” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Alterstum Kunde 70:25-35.

Daressy, G. (1893) “Recueil de cônes funéraires.” Mémoires publiés par les membres de la Mission archéologique français au Caire, 8.

Davies, N. (1938) “Some representations of tombs from the Theban necropolis.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 26:25-40.

Davies, N. de G. and M.F.L. Macadam (1957) A corpus of inscribed Egyptian funerary cones. Griffith Institute, Oxford.

Martin, G.T. and C.N. Reeves (1987) “An unattested funerary cone.” Göttinger Miszellen 95:63-64.

Reeves, C.N. and D.P. Ryan (1987) “Inscribed Egyptian funerary cones in situ: an early observation by Henry Salt.” Varia Aegyptiaca 3(1)47-49.

Petrie, W.M.F. (1888) A season in Egypt. Field and Tuer, London.

Stewart, H. (1986) Mummy cases and inscribed funerary cones in the Petrie collection. Aris and Phillips, Warminster.

Wiedemann, A. (1885) “Die altägyptischen Grabkegel.” Actes du sixième congrès international des orientalistes, 1883, Leide 4:131-155.