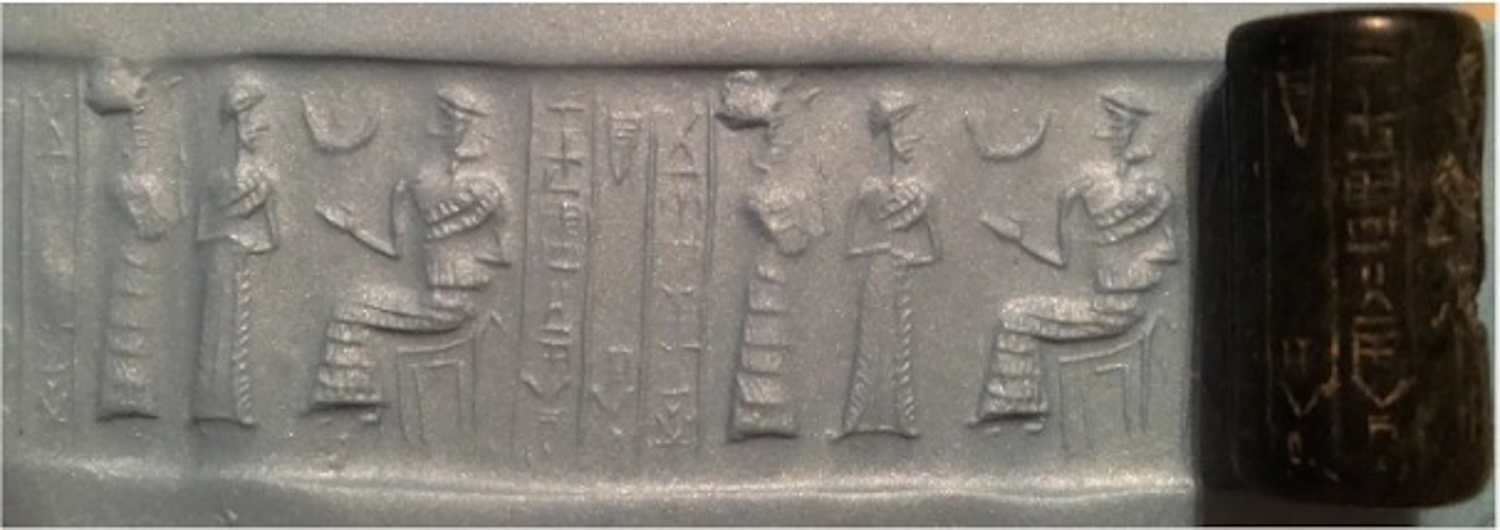

One of the most remarkable and well-preserved treasures from the ancient world, when increasingly sophisticated and well-organized civilizations began to emerge in the Near East, are carved stone seals in the shape of a cylinder, bearing a wide range of scenes and inscriptions that reflect the material culture, natural environment, political organization and the gods and goddesses of their time.

References

i The earliest archeological evidence for the use of cylinder seals comes from the thrash pits of a small site in southwestern Iran called Sharafabad, where impressions of engraved cylinder seals were found mixed with Middle Uruk pottery dated to around 3700. From slightly later, both at the large site of Uruk (modern Warka in southern Mesopotamia and at Susa (biblical Shushan, modern Shush) in Iranian Khuzestan, we find preserved the full range of administrative documents and tools, including abundant evidence for seals. While locks for the doors for storage rooms and sealings over the cords securing the contents of vessels and other containers continued to be marked with seals, the Uruk and Susa evidence clearly indicates a need to record information that would soon lead to the invention of writing. Cylinder seals are closely associated with that process.

From: http://enenuru.proboards.com/thread/194/cylinder-seals#ixzz4uk5hOSIk

ii Gibson, McG and R.D. Biggs (eds.) 1977. Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 6, Malibu